Modernizing the Models and Tools Used to Develop and Test New Drugs

For every new medicine that makes its way to market, many animals are killed. Although neither companies nor the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report any numbers, the total is likely to be in the millions every year.

Dogs, mice, rats, nonhuman primates, cats, rabbits, pigs, guinea pigs, and other animals all make the list. These animals undergo painful experiments that would be prosecutable as cruelty if they occurred outside the protected walls of scientific laboratories.

One could make a purely ethical argument for change, but there are valid reasons to abandon animal pharmaceutical testing beyond ethics alone. Human patients need safe and effective medications. Most human diseases have no treatment, despite billions of research dollars spent year after year. When effective treatments are developed, many include a long list of undesirable side effects. The FDA and the pharmaceutical industry recognize that it is time to do better than animal tests; they both acknowledge the need for human-specific approaches to study human outcomes. Moving from acknowledgement to acceptance of human-specific approaches in lieu of animal tests requires action from all stakeholders.

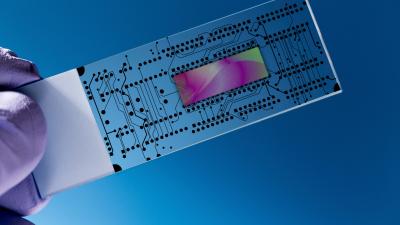

Thanks to innovation, creativity, and dedication, many scientists have developed new approaches that do not use animals. These human-specific approaches are more relevant to humans because they utilize human cells, tissues, and data, and allow researchers to model complexity and population diversity in ways that animal testing never could. Examples include advanced methods that are available for use today, like organs-on-chips, reconstructed tissue models, and computer simulations, as well as methods in development that use patient-specific information to create virtual digital patients.

Despite advances in human-specific methods, there are many factors that keep animal experiments in place in drug development. In 2017, Physicians Committee staff began hosting roundtable discussions with participants from the FDA, NIH, academia, and pharmaceutical industry to identify the barriers and to map a plan to overcome them. Factors discussed include inertia at companies and at the FDA, a lack of training in nonanimal methods, a lack of funding, and policies that require or favor animal tests. For drug development, policy includes laws passed by Congress and regulations and guidance developed by the FDA.

STATUTE

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the law that gives the FDA the authority to oversee drug development, references animal testing. Recently, members of the United States House of Representatives and Senate introduced a bill called the FDA Modernization Act to amend the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to remove certain references to animal testing. Surely, removing all statutory references to animal testing will be an important step toward achieving replacement.

REGULATIONS

Along with amending federal law, ending animal testing is impossible unless the Food and Drug Administration changes its own policies. Many FDA regulations, which are binding rules set by the agency to guide drug development, require and/or prioritize animal experiments, without providing flexibility for submission of data from nonanimal methods. For example, 21 Code of Federal Regulations Section 312.23(a)(5)(ii) requires that drug developers provide to the FDA “a summary of the pharmacological and toxicological effects of the drugs in animals, and, to the extent known, in humans.” In 2018, the Physicians Committee identified 235 regulations that prioritize or mandate animal experiments and proposed that the regulations be modified by switching out the word animal for nonclinical, which then clearly allows for use of nonanimal approaches. The Physicians Committee worked for years to inform Congress of the need to move away from animal experiments for human drugs. Last year, Congress passed Appropriations report language that directed the FDA to make the regulatory updates to clearly reflect the FDA’s discretion to accept nonanimal approaches. Along with our allies in Congress, we will continue working to ensure that this directive is met.

GUIDANCE

FDA guidance are recommendations issued by the agency to reflect the agency’s thinking on different topics. While guidance are non-binding, they can have the effect of regulations because they communicate the agency’s expectations to drug developers. FDA guidance recommend drug developers use at least two species (one rodent, one nonrodent), and many enumerate animal tests that use a variety of animals, while stating that alternative methods can be used where appropriate. Unfortunately, guidance also contain language stating that alternative methods can be used where the statutes and regulations allow for it, which nullifies any intended flexibility to use nonanimal methods, because the regulations currently require animal data.

When policies change, scientific practices can be expected to change. One FDA guidance updated in 2015 explicitly states that the agency no longer sought use of live rabbits for a certain type of testing, instead noting that sponsors could use ex vivo or in vitro approaches. The Physicians Committee reviewed FDA documents and found that, after this guidance, some companies used the ex vivo and in vitro tests instead of the animal test, although we cannot know for sure whether the guidance resulted in change because data available in publicly-available FDA documents are limited, and study dates are not consistently provided. Nevertheless, we hope to see additional explicit communications from the FDA reflecting a desire to not see data from certain animal tests, and instead recommending nonanimal approaches.

Until recently, there hasn’t been a clear way for nonanimal methods to gain the FDA’s stamp of approval, a concept for which the Physicians Committee has advocated for years. This changed when the FDA launched its Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs (ISTAND) pilot program in December 2020. ISTAND provides a pathway for companies and the FDA to work together to qualify nonanimal methods. Importantly, methods qualified under ISTAND will be communicated to sponsors via agency guidance indicating that the method can be used for its qualified purpose without the usual need for companies to do extensive validation work to use a new method. In the program’s first year, multiple companies have contacted the agency seeking to begin the process.

Despite all the inertia pushing for business as usual, revolutionary advances have been made in human-specific approaches that can reduce and replace animal use. When policies and funding shift to favor human-specific nonanimal approaches over animal experiments, the American public can expect safer and more effective drugs to be developed faster and at a lower cost—financially and morally.