How Science Can Spare Aquatic Animals

Aquatic animals include not just fish but also amphibians, marine mammals, crustaceans, reptiles, mollusks, aquatic birds, aquatic insects, starfish, and corals.

Aquatic animals face a wide variety of threats, including the destruction of their ecosystems, human consumption, and their use in research, testing, and medical products. Nonanimal research and testing methods and products are far and away better options than the commonly used cephalopods, sharks, and horseshoe crabs. They are more effective, more efficient, more reliable, more humane, and more responsible.

Cephalopods

Cephalopods are a class of mollusks that include octopuses and squids. Due to the fact that they are invertebrates, cephalopods are not covered by the U.S. animal welfare laws and regulations that affect federally-funded laboratories. This is contrary to international guidelines for cephalopod care and welfare in research.

Today, cephalopods, which have been known to unscrew jars to get food, carry shells as armor, and even escape from captivity, are used in health-related research that includes studies of RNA editing and bacterial colonization. These phenomena play important roles in human health and disease, but their investigation should utilize human samples, tissues, and cell cultures in order for advances to be relevant to human medicine.

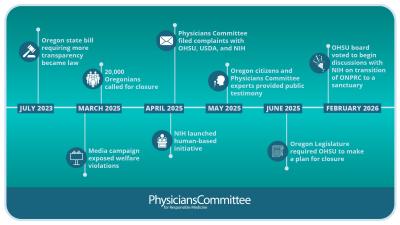

Researchers in the U.S. can capture, study, and kill cephalopods without approved protocols from ethics committees. Cephalopods are already protected by laboratory animal laws in Canada, the UK, New Zealand, and the EU. The Physicians Committee, in conjunction with several other groups, has petitioned the National Institutes of Health to include cephalopods as animals deserving of humane treatment under the public health service policy on humane care and use of laboratory animals and continues to work toward this goal.

Sharks

Squalene, a compound commonly sourced from sharks, is used as a cosmetic moisturizer and as a vaccine adjuvant. Adjuvants are a component of vaccines that work to boost the body’s vaccine-induced immune response. Shark-based squalene can only be extracted from the livers of dead sharks. Molecularly identical, nonanimal squalene sources that work just as well include olive oil, sugar cane, wheat germ, bacteria, and yeast.

About half of the shark species targeted for squalene are considered vulnerable to extinction, making manufacturer’s reliance on these animals not only unjustifiable but also short-sighted, especially as vaccine production increases and the demand for squalene grows. Plant-derived squalene is already available to meet vaccine adjuvant needs, but it’s up to pharmaceutical companies to make the switch. Regulatory agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can take action too by communicating the acceptability of plant-based and nonanimal-derived squalene and by encouraging companies to commit to using these alternatives.

Horseshoe Crabs

All injectable therapies and vaccines must be batch tested for fever-inducing contaminants before they are administered to humans. The default test uses blood of the horseshoe crab. A scalable, synthetic nonanimal test, called recombinant factor C (rFC), has been shown to be scientifically superior. Unfortunately, regulatory policies in the U.S lag behind the science and it is currently more burdensome to use rFC than the traditional horseshoe crab blood test.

The European Pharmacopoeia has accepted rFC without the additional barriers that exist in the U.S, but most companies are global, so they default to conducting the test that is accepted by all regulators to avoid duplicative work. The U.S. Pharmacopoeia still does not accept rFC without extensive additional work that is not needed if they use the horseshoe crab test. Notably, the FDA has accepted rFC for certain Eli Lilly therapies, as this trailblazing company undertook extensive extra work in order to avoid using horseshoe crab blood. For two years, patients in the U.S. have been treated with injected drugs that were released based on safety data derived from rFC and no medical issues have occurred as a result.

The Physicians Committee is working directly with Congress and regulatory agencies to ensure that, in time, all batches of injectable drugs and vaccines, including those against COVID-19, are tested without horseshoe crab blood.